Race, gender and class: ayahs and amahs as “worker-passengers” in British ships 1890-1950

I'm honoured to be giving the Mike Stammers Memorial Lecture 2023. It explores maritime equality, diversity and inclusion. Understanding ayahs helps us understand an overlooked intersection of race, gender and class on ships in the past.

WHERE? Merseyside Maritime Museum, Liverpool

WHEN? Wed 24 May at 5.30pm BST.

COST? It's free. No need to book.

What am I saying?

New ideas about equality, diversity, and inclusion are enriching maritime historiography. Exploring transnational movement by a significant group of mobile subjects -- Asian nannies -- enables us to gain fresh understandings of how intersectionality worked on early 20C ships.

Thousands of Indian ayahs and amahs (Japanese, Chinese and Malaysian nannies) travelled round the British empire creating domestic comfort afloat. They were non-kin members of the Raj families they accompanied. (Pic shows ayah and other Asian members of This Durham Light Infantry household).

Thousands of Indian ayahs and amahs (Japanese, Chinese and Malaysian nannies) travelled round the British empire creating domestic comfort afloat. They were non-kin members of the Raj families they accompanied. (Pic shows ayah and other Asian members of This Durham Light Infantry household).

Voyages changed ayahs. In gendered, racialized and very hierarchical colonial times these non-white, poorly-educated, female domestic workers gained unusual mobility and motility.

Conversely, ayahs changed voyaging. For example, segregationist policies and practises led to ship’s architects creating ayahs’ bathrooms aboard.

This talk looks at ayahs and amahs as part of an under-researched group: worker-passengers. They were neither seafarers nor passengers -- but almost fish and

Such voyagers included maids, valets, bearers and governesses. Like all passengers these servants had paid-for tickets. But for them the trip was not a leisurely interlude; they laboured throughout the voyage for the family who paid for that ticket.

Ayahs' subjective, segregated and exceptional experiences differed from those of the maritime labourers who were directly employed by shipping companies.

Unlike Lascars who routinely serviced the vessel, ayahs were intimately connected to their bosses on relatively one-off voyages. In that way they were unlike the white stewardesses who did care work, processing multiple batches of human cargo on repetitious trips.

Ayahs’ own testimony is barely visible. They are usually nameless.

The quantitative evidence used in this talk includes the freshly-sorted data I have derived from passenger lists.

This numerical data is triangulated with:

This numerical data is triangulated with:

- genealogical information about ayahs’ employers

- varied travellers’ voyage descriptions

- newspaper reports of ayah-related crime

- recent interviews with ayahs’ (now elderly) carees.

The lenses used include those generated by the new international working party on ayahs and amahs. This contextualises ayahs along with today’s airborne chattels, often Filipinas. Such intimate care workers' oppressive conditions are now recognised by activists. (See activist poster).

Many ayahs sailed to and from Liverpool, including on Bibby, Clan, and Henderson Line ships.

Ayah Boutflower was one, on the Anchor Line's Roumania. In October 1892 she headed from Liverpool to Bombay.

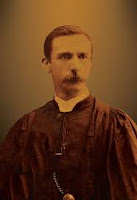

Almost certainly she was going to be dropped off in India while her employer, Edith Boutflower (pictured), sailed on to Australia to join her husband, William, there. He was a Seaforth lad made good, who had become a schools inspector in India.

Almost certainly she was going to be dropped off in India while her employer, Edith Boutflower (pictured), sailed on to Australia to join her husband, William, there. He was a Seaforth lad made good, who had become a schools inspector in India.

On the Roumania the ayah's job was look after Edith

and William's four children, including 8-month-old Margaret. Their paternal grandfather was the famous Seaforth vicar of St Thomas's, William Rawson.

Only nine people were saved from the wreck. (See an artist's idealised impression).

Glaswegian Elizabeth Burgess, with baby Arthur, was going back from Edinburgh to join her husband William (pictured), and their three children. She'd taken the baby to show her parents, taking a break from Wesleyan missionary work in Hyderbad.

It's likely that these ayahs had been making their first trip to England and had stayed for a few months with their employers' families of origin.

Baby Marjorie/Margaret Boutflower had been born in Jersey that January. Her mother may have travelled to Britain from Allahabad, the capital of North West Provincesith, the ayah, to have her baby 'at home' in the UK.

Expectant mothers sometimes did this, especially if they were frail, older or mistrusted the Indian health care system. Edith Butflower had already lost two children. Maybe she had been supported through that by this same ayah.

CONNECTING TO MIKE STAMMERS

The late Mike Stammers, AMA,FSA, a former keeper of the museum, was someoneI knew. My mum was delighted to give him many of her photos of the dock road gates at sunset. He would have enjoyed this talk.I myself am a Scouser, of a Liverpool seafaring family. My great-grandad Peter Quinn, a ship's barber, would have sailed with ayahs. Maybe he cut their hair with the scissors now on diplay in the museum that Mike helped create.

EXPLORING MORE

- You can read my work about ayahs and ethnic minority seafarers at http://jostanley.biz/ethnic_minorities.html

- The Roumania history is at https://www.bhsportugal.org/uploads/fotos_artigos/files/TheSSRoumania.pdf