LGBT+ seafarers in UK really have no maritime union heroes. I've looked hard. By contrast, in the US the National Union of Cooks and Stewards (known as the MCS for short) had a number of out activists who were 'queens.' The term was less rude than 'queer'.

The main two heroes, who remain legends, were Frank McCormick (1891-1980) (right) and 'Mickey' Blair (1917-1997). Mickey and Frank were life partners too. And they both loved dressing up and performing as women when informal theatrical opportunities were on offer.

Frank was an official and on the MCS executive. Mickey (Stephen) was a rank-and-file activist. Both were stewards, who lived in ship's gloryholes (cramped dormitories), worked 90-hour weeks, and believed in justice.

Frank was an official and on the MCS executive. Mickey (Stephen) was a rank-and-file activist. Both were stewards, who lived in ship's gloryholes (cramped dormitories), worked 90-hour weeks, and believed in justice.

Both had been dismised for 'homosexuality'. In Frank's case the US Navy dumped him in the 1920s.

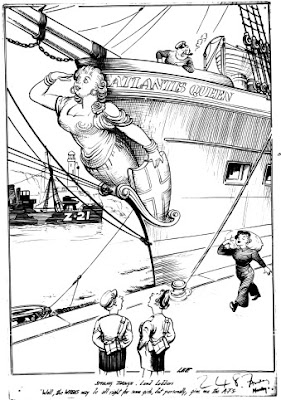

Among the ships Frank and Mickey worked on were Matson Line passenger vessels from California. such as the Lurline (pictured). Matson ships were known to be sites of camp subculture.

Matson, like some UK companies, liked having gay stewards because of their perceived “feminine touch". Also companies didn't want to employ black stewards. As heterosexual white stewards wouldn't work for the low pay on offer, so willing white GBT men provided employers with a solution.

UK similarities

- The nearest UK equivalent to Frank and Mickey is an unnamed member of NUMAST. In July 1994 this person tried to start the support group, Shore Leave. They appealed via the union's journal. Nothing seems to have got off the ground.

- The UK's main ex-seafaring activist was Mick Belsten (pictured far right, below) (1934-90). A former P&O steward, Mick became a Gay Liberation Front media worker after he'd left the sea. GLF was influenced by some of its founders' visits to the US. If Mick did ever try to encourage his union to be more progressive his efforts don't appear in any National Union of Seaman records. Mick Belsten NUS GLF

Why no progressive LGBT+ heroes?

That lack of inspiring figures seems counter-intuitive when some ships - like theatres - were the most camp workplaces in the world, c1950-1985. Floating "queer heavens" were key sites of proud informal solidarity and education.

But in those times trade unions were not so supportive of DEI as they are today. Men who were tough resisters of homophobic oppression at sea might well have recognised that shore-based formal trade union activity wouldn't have been effectve or as satisfying as workplace change-making.

Attacks on activists in US

In the US the MCS was totally different to the usual pattern. The union had thrived in the 1930s and in WW2, precisely because it was indeed inclusive. Membership jumped threefold to 15,000 from Frank's starting time.

Then a post-war and Cold War backlash began. The rationale was that 'fruits' were a threat to national security. Race was not the issue; 'moral decay' and 'Communism' was.

As a result, the new Port Security Act said the Coast Guard must officially screen seafarers joining ships: one by one, every trip.

In Los Angeles on Monday November 6th 1950, Mickey, Frank and some comrades were hit by the anti-gay hysteria besetting the nation. They walked up the gangway of the Matson Liner Lurline (nicknamed the Queer-line), ready to work their way to Hawaii.

But in all eighteen cooks and stewards were turned back including Mickey, although oddly not Frank. That might have been 20% of the catering workers aboard.

The ensuing fight-back focused on 'The Lurline Eighteen' case became a cause celebre. Scotty Ballard, a gay black steward, (pictured) led the multiracial Seamen's Defence Committee, which worked in conjunction with the longshoremen and the MCS.

Scotty and his gay white friend Ted (Riff-Raff) Rolfs, created leaflets, sent letters, and picketed the Coast Guard offices.

But by January 1951 almost every leff-wing steward from US West Coast ships had been removed. Three quarters of them were African American. An unknown number of the screened-off people were gay. All were progressives.

It was the start of the end for the MCS. Like other left-wing US unions, it was defeated, not least by the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act.

UK: different focus

In the UK the progressive activism was against right-wing rectionary policies, rather than against homophobia, which was not mentioned. Race continued to be a thorny matter, during and after WWII.

Preparing for the 1967 Sexual Offences Act meant that the NUS had to speak about homosexuality. It was not progressive.

By then a new breed of gay activist was emerging: not apologist or apolitical, but confrontational, libertarian, and aware of gender politics. Mick Belsten in London was challenging homophobia but not with maritime workplaces in mind.

Seafaring had taught him a transferrable skill: how to organise and enjoy solidarity. He wasn't involved in shipping now in any way but because he had travelled so much he was able to enjoy thinking as an internationalist.

In the wider UK, it took until the 1970s for unions to start backing LGBT+ rights, including unfair dismissals. This was a time of new anti-racism activism too. The developments were asymetrical.

At the weekly Gay Liberation Front meetings that Mick Belsten attended 200-300 were there. Though the radicalism in LGBT+ politics declined in the 1980s, in the 1990s uneven action for minority rights really took off, especially in local government and teachers' unions.

Interweaving strands

Over in the US Frank and Mickey were aware of the changed climate created by the 1969 Stonewall riots, just as Mick was in newly-pink London.

Frank died in 1980, just before AIDS changed gay seafarers' views of their sexual safety in foreign ports.

Mick was by then a very effective radical journalist. In 1990 he fell victim to an AIDS-related illness, just four years before the attempt to initiate the Shore Leave support group in 1994.

Mickey died in 1997. He surely never knew about Shore Leave, but would have been happy to advise on tactics.

He was always pressurising Allan Berube, his union's historian, to make sure the full story of the MCS was told. Allan did so, many times, before he died in 2007. His records are crucial to the world knowing just how extraordinary this maritime activism was.

FAQs

How come a union in any country could be supportive of LGBT+ in those early days? It was a time of general progressive support for justice for marginalised people, including black workers. We'd call it intersectionality today.

What Frank and Mickey do? On their ships and in union headquarters they oranised, challenged, supported. The union even had its own hiring hall, to bypass shipowners.

Were Mickey and Frank acclaimed in their lifetime? They were appreciated. This was not a union that went in for hero worship, or for making activists union presidents.

What did Mickey and Frank do when the union was demolished? They settled in Seattle and were still involved in gay community theatre.

--

Are you looking for more information? Try:

Virtually: The Stephen R. Blair papers, including photo albums, can be seen at at the University of Washington Special Collections. This archive can be visited virtually, by appointment: Blair pics

On paper: see Allan Berube, My Desire for History: Essays in Gay, Community,and Labour History, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2011, Chapter 16.

Browsing:

US. Waterfront Workers History Project, Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies, Waterfront

UK. Roger Rosewell, The Seamen’s Struggle, Part II: The Fight for Reform, 1973, Minority_Movement